What Are Neutron Stars?

Neutron stars are among the most extreme and densest natural objects known in the universe. They form after a massive star undergoes a violent transformation at the end of its life, representing cosmic structures where matter is compressed to the very limits of what we understand. A neutron star can have a mass greater than the Sun’s, yet be confined within a diameter of only a few tens of kilometers. This extraordinary density makes neutron stars natural laboratories where the most extreme physical conditions in the universe can be observed.

The internal structure of a neutron star is so dense that it cannot be compared to any material encountered in everyday life. In these stars, matter is compressed beyond the normal structure of atoms. Under tremendous pressure, electrons and protons combine and turn into neutrons. As a result, most of the star becomes an incredibly dense body made primarily of neutrons—the feature that gives neutron stars their name. The density is so immense that a teaspoon of neutron-star material on Earth would be calculated to weigh billions of tons.

Neutron stars are remarkable not only for their density, but also for their powerful gravity. The surface gravity is billions of times stronger than Earth’s. This intense pull noticeably warps the surrounding spacetime and can cause even light escaping from the surface to lose energy. For this reason, neutron stars are among the objects where effects predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity can be observed directly.

Physically, neutron stars are extremely compact. A typical neutron star has a diameter of around twenty kilometers, while its mass can be close to—or even exceed—the Sun’s mass. This raises an obvious question: why doesn’t it keep collapsing into a black hole? What supports a neutron star against further collapse are quantum-origin repulsive forces between neutrons. These forces provide the balance needed to counteract the star’s own gravity.

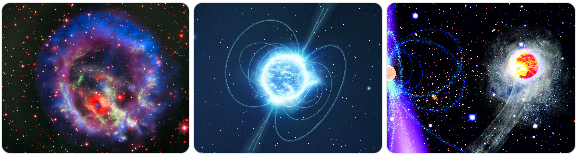

Neutron stars also rotate extremely rapidly. Because the core shrinks suddenly during formation, angular momentum is conserved and the star reaches very high spin rates. Some neutron stars can rotate tens or even hundreds of times per second. This rapid rotation directly influences how neutron stars interact with their surroundings and how they appear in observations.

Magnetic fields are another defining feature of neutron stars. Their magnetic fields are among the strongest known in the universe. These fields can channel high-energy radiation emitted from the star’s surface and, in some neutron stars, lead to the emission of regular signals. Such properties form the basis for dividing neutron stars into different subtypes.

Neutron stars represent one of the final stages of stellar evolution. Being among the densest remnants a collapsing star can leave behind makes them a critical part of the cosmic cycle. They matter not only as individual objects, but also as keys to understanding how matter and energy behave under extreme conditions.

In conclusion, neutron stars represent one of the most extreme states matter can take in the universe. With their incredible density, powerful gravity, rapid rotation, and extraordinary magnetic fields, they push the limits of known physics. Studying neutron stars means understanding not only how stars die, but also how far the fundamental laws of the universe remain valid.