How Do Comets Form?

The formation of comets begins in a very early era that reaches back to the birth of the Solar System. When the Sun was still forming, a vast disk of gas and dust surrounded it. This disk provided the raw material for all planets, moons, and small bodies in the Solar System. Comets formed within this original disk, especially in regions far from the Sun where temperatures were extremely cold.

Close to the Sun, high temperatures caused volatile substances to evaporate, so bodies made mostly of rock and metal formed there. Farther from the Sun, however, temperatures were low enough for materials such as water, carbon dioxide, methane, and ammonia to remain frozen. The ices that define comets’ composition accumulated in these distant, frigid zones.

In those outer regions, tiny grains of ice and dust gradually collided and stuck together, building larger bodies over time. This process is extremely slow and continued for millions of years. The resulting primitive objects were not large enough to become planets, but they were stable enough to preserve early Solar System material. Comet nuclei formed through this gradual growth.

After formation, many of these bodies remained in the outer Solar System. The Sun’s gravity and the influence of the newly forming giant planets shaped the orbits of these small icy objects. In particular, the strong gravity of the giant planets scattered some comets onto very distant orbits. This is one of the main reasons comets often have long, highly elliptical paths today.

While some comets stayed in more orderly outer regions, others were sent to extremely remote distances. In those far-off regions, comets can survive for billions of years with very little change. Because they remain so far from the Sun, they do not warm up, and their ices are largely preserved. In this sense, comets are like frozen remnants of the Solar System’s earliest state.

From time to time, the orbits of comets in these distant reservoirs can be disturbed. A passing star, the gravitational pull of the galaxy, or interactions with giant planets can redirect them toward the Sun. A comet may then begin a long journey into the inner Solar System after an immense period of quiet. During much of this journey, the comet remains dark and inactive.

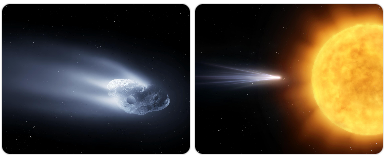

Once a comet approaches the Sun closely enough, its icy structure—gained during formation—becomes active. Frozen materials warm up and turn into gas, creating a broad cloud of gas and dust around the comet. At this point, the comet becomes a bright object in the sky for the first time in billions of years. This brightness is not the comet’s “birth,” but the visible phase of a long evolutionary history.

Understanding how comets form is crucial not only for learning about comets themselves, but also for understanding how the entire Solar System took shape. Comets carried primitive materials that were not incorporated into planets and preserved them to the present day. Each comet is therefore a natural archive opening a window into the Solar System’s earliest eras.

In conclusion, comets are icy bodies that formed in the cold, distant regions of the young Solar System. Remaining largely unchanged for billions of years, they can create spectacular tails when conditions bring them close to the Sun. Their modern appearance is a temporary, luminous expression of an ancient formation process.